I’m currently reading Scott Brinker’s book Hacking Marketing: Agile Practices to Make Marketing Smarter, Faster, and More Innovative (awesome book – look for a much more complete review here soon) and came across a line in Chapter 7 that says “Be pragmatic, not dogmatic.”

I’m currently reading Scott Brinker’s book Hacking Marketing: Agile Practices to Make Marketing Smarter, Faster, and More Innovative (awesome book – look for a much more complete review here soon) and came across a line in Chapter 7 that says “Be pragmatic, not dogmatic.”

This really spoke to me.

One of the things I dislike about many business books is that they try to create dogma and that readers should follow their ‘recipe’ and you’re business will be ‘great’. Much like Isaac Sacolick’s Driving Digital (see my review of Isaac’s book here), Scott doesn’t do that with his book…instead he’s telling people to stop trying to find a recipe that other companies have used for success and start from scratch (with lessons learned from others of course).

One of the most damaging routes a company can take is trying to mimic another. I’ve been in meetings listening to product managers describe their product roadmap that contains 99% ‘me too’ features to keep up with their competitors. When I ask about innovation, I get blank stares. These folks are stuck in the dogma of their industry and their organization. They are focused on imitation rather than innovation.

That’s where being pragmatic comes into play. Sure…there may be features that you must have to compete in your vertical/industry but if you’re entire roadmap is focused on imitation, its time to take a step back and rethink your approach, your investment and your business. Rather than mimic everything others are doing (e.g., being dogmatic), take a the pragmatic approach. Take a look at what your competitors are doing, what your clients want, what you can deliver and what best fits into your organization’s long-term goals and then do that.

Another aspect of pragmatic vs dogmatic that I see often is that of project management. How many times have you heard (or said!) “well…we need to build a gantt chart before the project can start” or “that’s not how the PMBOK” says to do it or ‘Scrum requires us to do X, Y and Z in that order.” That’s dogmatic. Not every project requires a gantt chart or a daily 15min standup meeting. Not every organization can (or should) follow the dogma of project management methods. The most successful project managers out there are those that know when to follow guidelines and when to deviate from said guidelines.

So…be pragmatic, not dogmatic. Thanks for the quote Scott.

from Eric D. Brown http://ericbrown.com/be-pragmatic-not-dogmatic.htm

http://ericbrown.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/prag350x233-300x200.jpg

2017 has been the year of AI, reaching a fever pitch of VC and corporate investment. But, as with any hot technology, AI is outgrowing this phase of experimentation and hype. According to research firm Gartner, we’re past the “peak of inflated expectations.” Next up is a necessary recalibration of the space—one that will separate the winning AI-driven companies from all… Read More

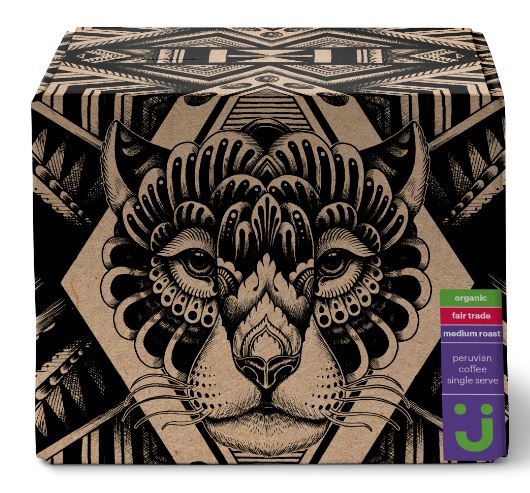

2017 has been the year of AI, reaching a fever pitch of VC and corporate investment. But, as with any hot technology, AI is outgrowing this phase of experimentation and hype. According to research firm Gartner, we’re past the “peak of inflated expectations.” Next up is a necessary recalibration of the space—one that will separate the winning AI-driven companies from all… Read More Walmart’s Jet.com is going after millennials shoppers with the launch of its own grocery brand called Uniquely J, which is expected to arrive in a couple of months. The goal with the brand – beyond an obvious desire for increased margins – is to attract a younger shopper. Jet believes that Uniquely J will do so not only by nature of a product selection that includes…

Walmart’s Jet.com is going after millennials shoppers with the launch of its own grocery brand called Uniquely J, which is expected to arrive in a couple of months. The goal with the brand – beyond an obvious desire for increased margins – is to attract a younger shopper. Jet believes that Uniquely J will do so not only by nature of a product selection that includes…  Multiple sources tell TechCrunch that Google is building a tabletop smart screen for video calling and more that will compete with Amazon’s Echo Show. The device could help Google keep up in the race for the smart home market after Amazon just revealed a slew of new Echos and as Facebook continues to work on its codename “Aloha” video calling screen. Two sources confirm to…

Multiple sources tell TechCrunch that Google is building a tabletop smart screen for video calling and more that will compete with Amazon’s Echo Show. The device could help Google keep up in the race for the smart home market after Amazon just revealed a slew of new Echos and as Facebook continues to work on its codename “Aloha” video calling screen. Two sources confirm to…  Today, Amazon threw a lot of darts at the smart speaker board with new product offerings that are seeking to explore what smart speakers can even do. A report also emerged today from 9to5Google that Google is seeking to build a high-end “max” version of its Home speaker, news that comes just a week before the company is likely to show off a cheaper “mini” version of…

Today, Amazon threw a lot of darts at the smart speaker board with new product offerings that are seeking to explore what smart speakers can even do. A report also emerged today from 9to5Google that Google is seeking to build a high-end “max” version of its Home speaker, news that comes just a week before the company is likely to show off a cheaper “mini” version of…  The Amazon Echo Connect will connect Echo devices to landline phones. Yes, a landline because safety. The thought is with this add-on Echo owners will be able to dial telephone numbers, like 911 or Pizza Hut or Mom, by just using their voice. To do this, the device connects to a home phone system through RJ-11 jacks. It uses the line’s existing phone service to handle the dialing. This…

The Amazon Echo Connect will connect Echo devices to landline phones. Yes, a landline because safety. The thought is with this add-on Echo owners will be able to dial telephone numbers, like 911 or Pizza Hut or Mom, by just using their voice. To do this, the device connects to a home phone system through RJ-11 jacks. It uses the line’s existing phone service to handle the dialing. This…  When Amazon beat out Twitter and Facebook to stream the NFL’s Thursday Night Football series this season, people were pretty surprised. The one year deal, which requires viewers be Amazon Prime member, will show 11 games this season starting tonight with the Bears playing the Packers at 8:25pm ET. Here’s how to watch it if you’re a Prime member: If you have a Fire TV or…

When Amazon beat out Twitter and Facebook to stream the NFL’s Thursday Night Football series this season, people were pretty surprised. The one year deal, which requires viewers be Amazon Prime member, will show 11 games this season starting tonight with the Bears playing the Packers at 8:25pm ET. Here’s how to watch it if you’re a Prime member: If you have a Fire TV or…  Alexa’s voice-activated apps will now have a new way to alert end users about updates and new content, Amazon announced today. Thanks to newly added Notifications functionality, Alexa skill developers can configure their voice app to change the color of the LED on an Alexa-powered device and play an audio cue when a notification for their voice app is available. A small handful of…

Alexa’s voice-activated apps will now have a new way to alert end users about updates and new content, Amazon announced today. Thanks to newly added Notifications functionality, Alexa skill developers can configure their voice app to change the color of the LED on an Alexa-powered device and play an audio cue when a notification for their voice app is available. A small handful of…  I’m currently reading

I’m currently reading  Along with yesterday’s announcements of a half-dozen new gadgets, including new Echo devices, Amazon also detailed some of Alexa’s new abilities, due to arrive in the near future. One of the more interesting additions, arriving this fall, is something called “Routines.” Designed primarily for those interested in automating their smart home with simpler commands,…

Along with yesterday’s announcements of a half-dozen new gadgets, including new Echo devices, Amazon also detailed some of Alexa’s new abilities, due to arrive in the near future. One of the more interesting additions, arriving this fall, is something called “Routines.” Designed primarily for those interested in automating their smart home with simpler commands,…  Social media giants have again been put on notice that they need to do more to speed up removals of hate speech and other illegal content from their platforms in the European Union. The bloc’s executive body, the European Commission today announced a set of “guidelines and principles” aimed at pushing tech platforms to be more pro-active about takedowns of content deemed…

Social media giants have again been put on notice that they need to do more to speed up removals of hate speech and other illegal content from their platforms in the European Union. The bloc’s executive body, the European Commission today announced a set of “guidelines and principles” aimed at pushing tech platforms to be more pro-active about takedowns of content deemed…  The message of today’s big Amazon event was pretty clear: Echos for everyone, for every need in every room of every home. The company clearly has no desire to create one device to rule them all. Instead, it’s building out micro functionality, with every product designed to target different needs for different users.

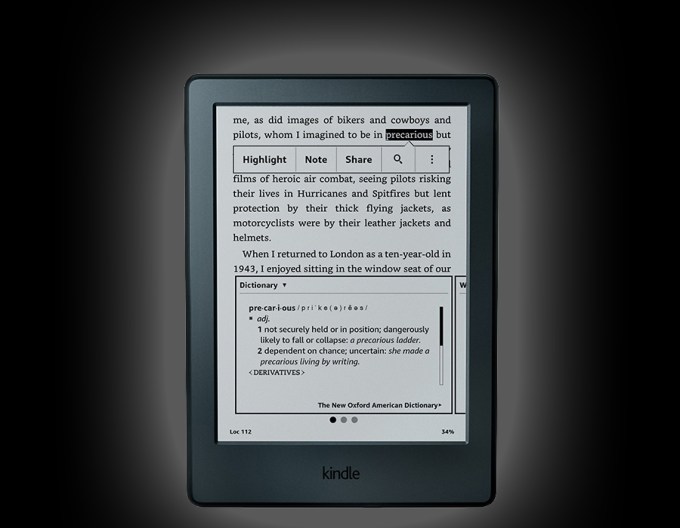

The message of today’s big Amazon event was pretty clear: Echos for everyone, for every need in every room of every home. The company clearly has no desire to create one device to rule them all. Instead, it’s building out micro functionality, with every product designed to target different needs for different users.  Amazon launched so much new stuff today that I can’t even remember what they all are (there might’ve been a fish in there, even) but there was a glaring omission in the slate of reveals: The Kindle. Amazon’s e-reader has a long and successful track record, with each successive model and iteration bringing some nice changes to the table, but the last big change came out in…

Amazon launched so much new stuff today that I can’t even remember what they all are (there might’ve been a fish in there, even) but there was a glaring omission in the slate of reveals: The Kindle. Amazon’s e-reader has a long and successful track record, with each successive model and iteration bringing some nice changes to the table, but the last big change came out in…  Along with Amazon’s numerous Echo-related announcements today regarding new devices, the company also said it would soon be extending and improving its hands-free TV viewing experience to a range of video partners, including big names in streaming services like Hulu, PlayStation Vue, CBS All Access, Showtime, and others. Prior to now, Amazon had been working on making Alexa a…

Along with Amazon’s numerous Echo-related announcements today regarding new devices, the company also said it would soon be extending and improving its hands-free TV viewing experience to a range of video partners, including big names in streaming services like Hulu, PlayStation Vue, CBS All Access, Showtime, and others. Prior to now, Amazon had been working on making Alexa a…  In a day full of Echo announcements, the Echo Button was a clear standout. Not because it was a better or more useful product than the rest, but because it’s just damn weird. Where most of what the company announced today was some iteration on an existing product line (be it the Echo or Fire TV), the Button is a strange, left field offering with a limited case use. More than any…

In a day full of Echo announcements, the Echo Button was a clear standout. Not because it was a better or more useful product than the rest, but because it’s just damn weird. Where most of what the company announced today was some iteration on an existing product line (be it the Echo or Fire TV), the Button is a strange, left field offering with a limited case use. More than any…  Whether you call it fragmentation or flexibility, there’s now seven different Amazon Echo devices to choose from. Today Amazon launched a slew of new smart home devices so there’s one for every conceivable use case and living set-up. That leaves competitor Google Home looking like a one-size-fits-none solution. Now there’s the Echo for audiophiles, Look for fashionistas, Dot…

Whether you call it fragmentation or flexibility, there’s now seven different Amazon Echo devices to choose from. Today Amazon launched a slew of new smart home devices so there’s one for every conceivable use case and living set-up. That leaves competitor Google Home looking like a one-size-fits-none solution. Now there’s the Echo for audiophiles, Look for fashionistas, Dot…  Amazon went above and beyond today in terms of launching stuff – it debuted not one, not two, but six brand new devices at an event held at its HQ. One of the most interesting things it did today was not any particular piece of hardware it designed or built – but the way it’s selling the Echo Plus, the version of its Echo smart speaker with an integrated smart home hub. The…

Amazon went above and beyond today in terms of launching stuff – it debuted not one, not two, but six brand new devices at an event held at its HQ. One of the most interesting things it did today was not any particular piece of hardware it designed or built – but the way it’s selling the Echo Plus, the version of its Echo smart speaker with an integrated smart home hub. The…