Ask someone what they do, and they'll probably talk about where they work. "I work in insurance," or even, "I work for Aetna."

Of course, most of the 47,000 people who work for Aetna don't do anything that's specifically insurance-y. They do security for Building 7, or they answer the phone for someone, or they work in the graphic design department.

Most people have been trained to come to work in search of familiarity and competence. To work with familiar people, doing familiar tasks, getting familiar feedback from a familiar boss. Competence is rewarded, coloring inside the lines is something we were taught in kindergarten.

People will do a bad (a truly noxious) job for a long time because it feels familiar. Legions of people will stick with a dying industry because it feels familiar.

The reason Kodak failed, it turns out, has nothing to do with grand corporate strategy (the people at the top saw it coming), and nothing to do with technology (the scientists and engineers got the early patents in digital cameras). Kodak failed because it was a chemical company and a bureaucracy, filled with people eager to do what they did yesterday.

Change is the unfamiliar.

Change creates incompetence.

In the face of change, the critical questions that leaders must start with are, "Why did people come to work here today? What did they sign up for?"

That's why it's so difficult to change the school system. Not because teachers and administrators don't care (they do!). It's because changing the school system isn't what they signed up for.

The solution is as simple as it is difficult: If you want to build an organization that thrives in change (and on change), hire and train people to do the paradoxical: To discover that the unfamiliar is the comfortable familiar they seek. Skiers like going downhill when it's cold, scuba divers like getting wet. That's their comfortable familiar. Perhaps you and your team can view change the same way.

from Seth Godin's Blog on marketing, tribes and respect http://feeds.feedblitz.com/~/337005008/0/sethsblog~In-search-of-familiarity.html

Were you one of the many parents surprised to find hundreds of dollars’ worth of Smurfberries charged to your card a few years back? Amazon’s lax in-app purchasing requirements let kids all over the country buy coins and crystals to their hearts’ content, something the FTC frowned on. News that refunds would be available soon broke in April, and the time has come at last. Read More

Were you one of the many parents surprised to find hundreds of dollars’ worth of Smurfberries charged to your card a few years back? Amazon’s lax in-app purchasing requirements let kids all over the country buy coins and crystals to their hearts’ content, something the FTC frowned on. News that refunds would be available soon broke in April, and the time has come at last. Read More Surprisingly, Amazon Alexa doesn’t have a good way to search for Alexa skills by voice. You can’t say that you want to play word games, need a skill to check airport security wait times, or feel like meditating. Alexa doesn’t know what to tell you. Amazon released its own “Skill Finder” skill last year, but it’s a bare-bones experience that can only read off…

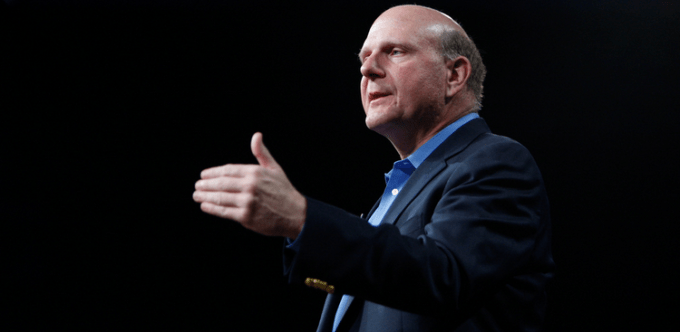

Surprisingly, Amazon Alexa doesn’t have a good way to search for Alexa skills by voice. You can’t say that you want to play word games, need a skill to check airport security wait times, or feel like meditating. Alexa doesn’t know what to tell you. Amazon released its own “Skill Finder” skill last year, but it’s a bare-bones experience that can only read off…  Former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer took the stage at Code Conference on Tuesday and talked about why he took a large position in Twitter. “There’s a real opportunity to make that a valuable economic asset,” said Ballmer, defending his decision to invest in what has been a volatile ride for the social media company. He believes in its potential because it “gives people…

Former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer took the stage at Code Conference on Tuesday and talked about why he took a large position in Twitter. “There’s a real opportunity to make that a valuable economic asset,” said Ballmer, defending his decision to invest in what has been a volatile ride for the social media company. He believes in its potential because it “gives people…  Amazon’s own take on a QVC-like home shopping experience, “Style Code Live,” has gone off the air. The live program, first launched in March 2016, was streamed online and via mobile to Amazon shoppers, who could learn about fashion and beauty tips from style experts, then instantly shop the products being featured on the show. Just ahead of the Memorial Day weekend here in…

Amazon’s own take on a QVC-like home shopping experience, “Style Code Live,” has gone off the air. The live program, first launched in March 2016, was streamed online and via mobile to Amazon shoppers, who could learn about fashion and beauty tips from style experts, then instantly shop the products being featured on the show. Just ahead of the Memorial Day weekend here in…  Amazon has officially begun operating its AmazonFresh Pickup locations in Seattle, letting customers order groceries ahead of time and then quickly grab them on their way home. The service requires as little as 15 minutes advance notice, without any minimum purchase requirements, and it’s a free service for any Amazon Prime members. Amazon first revealed Pickup back in March, but…

Amazon has officially begun operating its AmazonFresh Pickup locations in Seattle, letting customers order groceries ahead of time and then quickly grab them on their way home. The service requires as little as 15 minutes advance notice, without any minimum purchase requirements, and it’s a free service for any Amazon Prime members. Amazon first revealed Pickup back in March, but…