There's a difference between speed and acceleration. This is hard for novice physics students to grasp. Velocity (speed) is how fast you're going. Acceleration is a measure of how quickly you're getting faster.

Brands today are built on relationships, and relationships of all kinds work solely because of expectation. That thing we're confidently hoping we're going to get from that next encounter.

The shift we're facing is that expectation isn't the speed (the quality, the value, the repeatability of an interaction), it's now become more like the acceleration of it, the change in what we expect.

And so advertisers and fashion houses and singles bars and Hallmark cards are built on promises. The promise of what to expect next.

The challenge: Expectations change. A few good encounters and we begin to hope for (and expect) great encounters. Sooner or later, our expectation for a politician or a motorcycle company or a service we regularly engage in goes up so much it can't be met.

When the economy is racing forward, people are engaged and satisfied. When it slows, when the good news slows down, people are even less satisfied than they were when they had fewer resources.

A common ridiculous expression is, "expect the unexpected." Of course, once you do that, it's not unexpected any more, is it?

Expectation is in the eye of the beholder, but expectation is often enhanced and hyped by the marketer hoping for a quick win. And there lies the self-defeating dead end of something that would serve everyone if it were a persistent positive cycle instead.

from Seth Godin's Blog on marketing, tribes and respect http://feeds.feedblitz.com/~/186630776/0/sethsblog~Expectation-is-the-brand-killer.html

Salesforce earnings came out today! They’re not great, either, and it looks like a weak outlook for the company’s third quarter is doing some damage to its shares, which were down as much as 8 percent. For a company that literally defined the phrase “software as a service” — basically, running your business online — and one that’s had a decent year… Read More

Salesforce earnings came out today! They’re not great, either, and it looks like a weak outlook for the company’s third quarter is doing some damage to its shares, which were down as much as 8 percent. For a company that literally defined the phrase “software as a service” — basically, running your business online — and one that’s had a decent year… Read More Amazon’s growing shipping operation is profiled at length in a new Bloomberg feature, and the article paints a picture of the e-commerce giant putting together the pieces to build one of the largest and most effective global shipping operations in the world, from centralized distribution hubs, to bulk air transport, to last-mile front door delivery. While on the surface, Amazon is still…

Amazon’s growing shipping operation is profiled at length in a new Bloomberg feature, and the article paints a picture of the e-commerce giant putting together the pieces to build one of the largest and most effective global shipping operations in the world, from centralized distribution hubs, to bulk air transport, to last-mile front door delivery. While on the surface, Amazon is still…  Wireless speaker system maker Sonos announced two software partnerships today with Spotify and Amazon. The Spotify integration allows users to control their Sonos speakers via the Spotify app, essentially turning each Sonos speaker – or all of them – into a Spotify Connect system. The Sonos/Amazon partnership is a bit more interesting. Your Sonos speakers will be able to work…

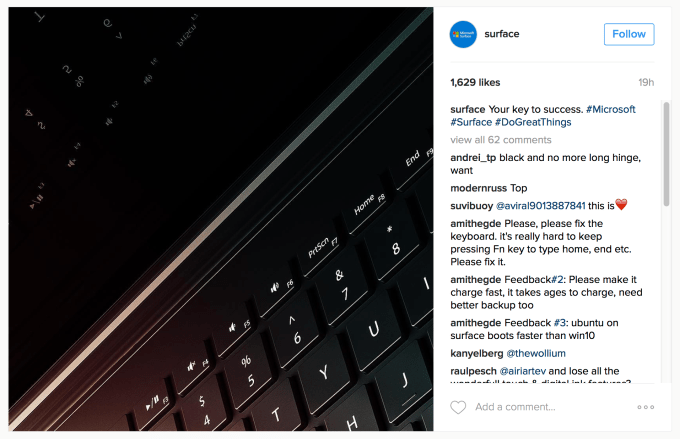

Wireless speaker system maker Sonos announced two software partnerships today with Spotify and Amazon. The Spotify integration allows users to control their Sonos speakers via the Spotify app, essentially turning each Sonos speaker – or all of them – into a Spotify Connect system. The Sonos/Amazon partnership is a bit more interesting. Your Sonos speakers will be able to work…  Generally, you don’t see the first spy shots of a new device coming from the company itself, but Microsoft isn’t really following all that many of the rules with its Surface lineup of house-built Windows hardware. That’s why it makes a certain kind of sense that the first look at what could be a Surface Book 2 comes from none other than Microsoft’s own official…

Generally, you don’t see the first spy shots of a new device coming from the company itself, but Microsoft isn’t really following all that many of the rules with its Surface lineup of house-built Windows hardware. That’s why it makes a certain kind of sense that the first look at what could be a Surface Book 2 comes from none other than Microsoft’s own official…  As China’s digital business grows, it’s going to provide more opportunities for many players. Who “gets it” and who doesn’t will certainly not only be a function of “being blocked or not,” but equally (or even more importantly) those who have the right mindset and approach to the China context.

As China’s digital business grows, it’s going to provide more opportunities for many players. Who “gets it” and who doesn’t will certainly not only be a function of “being blocked or not,” but equally (or even more importantly) those who have the right mindset and approach to the China context.  Artificial intelligence pops up as a buzzword every few years, but it has never moved beyond novelty status. This time, though, it is here to stay, and startups are poised to drive the AI economy forward.

Artificial intelligence pops up as a buzzword every few years, but it has never moved beyond novelty status. This time, though, it is here to stay, and startups are poised to drive the AI economy forward.  Retailers grasp the web-focused future of the industry, but the sale of Jet.com to Walmart earlier this month has sped up the shift and validated the online marketplace approach to e-commerce.

Retailers grasp the web-focused future of the industry, but the sale of Jet.com to Walmart earlier this month has sped up the shift and validated the online marketplace approach to e-commerce.