Last week, California governor Gavin Newsom announced that he was intending to aggressively scale back plans for the state’s high-speed rail system, which in its most ambitious routing would have connected Sacramento to San Diego. The immediate cause was ballooning costs, which have risen from $33 billion to $77 billion and looked likely to exceed 1.6 Zuckerbergs within a couple of years (the local CA currency, otherwise known as $100 billion).

Unlike other megaprojects, Newsom — and California — were fortunate on the timing. The costs of the project skyrocketed so much and so early, that Newsom still had the credibility and political capital to kill the project. And while a short route from Bakersfield to Merced remains on the table, I don’t expect even that route to be ultimately constructed, since no one knows where either of those cities are.

Why can’t we (i.e. America) build anything? High-speed rail isn’t Silicon Valley whizbang magic technology, it’s definitely not Hyperloop. It’s pretty standard in a bunch of industrialized nations around the world. Clearly that question was on the minds of reporters, because we have been inundated with autopsies on HSR. Yet, the hot takes don’t seem to be adding up to anything meaningful (surprise).

So, we are going to explore this question over the coming weeks, as one of our newest obsessions here at Extra Crunch.

This weekend, I read a book called “Politics across the Hudson: The Tappan Zee Megaproject.” In the book, Philip Mark Plotch chronicles the forty years of planning that led to the reconstruction of the Tappan Zee bridge, which connects Rockland and Westchester Counties north of New York City over the Hudson River. If you want to read about the weeds of government dysfunction around infrastructure, this is your book. It’s a telling tale of patterns we see repeatedly when trying to build great things in the United States:

- No one wants to talk about finance: Politicians love selling the value of a megaproject without actually discussing the ways they are going to have to pay for it. Yet, paying for it is the project, since it will ultimately affect how citizens enjoy the infrastructure.In the Tappan Zee case, politicians wanted to avoid talking finances because finances meant tolls, and increasing tolls meant losing elections. New York’s current governor Andrew Cuomo ends up avoiding this conversation through luck, as the state received huge indemnities from Wall Street banks related to Iranian money laundering and sanctions that helped fund the bridge (which one planner called “manna from god”).That avoidance has led to the “Willie Brown” model of infrastructure, named for the former San Francisco mayor who wrote about how to get infrastructure projects done:

News that the Transbay Terminal is something like $300 million over budget should not come as a shock to anyone.

We always knew the initial estimate was way under the real cost. Just like we never had a real cost for the Central Subway or the Bay Bridge or any other massive construction project. So get off it.

In the world of civic projects, the first budget is really just a down payment. If people knew the real cost from the start, nothing would ever be approved.

The idea is to get going. Start digging a hole and make it so big, there’s no alternative to coming up with the money to fill it in.

Of course, that model can lead to situations like Boston’s Big Dig, where the final ticket price for a project is so high, that it effectively bankrupts an entire city and its transportation system for years to come.

Infrastructure finance may not be a sexy topic, but it is absolutely critical to getting a project done. It’s hard to tuck tens of billions of dollars in a line item in the state’s budget, and it is hard to get the different funding levers of government involved when a project’s finances aren’t clear.

- Lack of direction / lack of leadership: Building infrastructure is hard. It’s even harder in the U.S., where a patchwork of regulatory bodies and all levels of government are involved in infrastructure decision-making. In the Tappan Zee bridge case, there were nearly two dozen agencies involved, all with their own agendas and fiefdoms. A dedicated bus lane on the bridge was cut to avoid bringing in the Federal Transit Administration. The Tappan Zee is built at one of the widest points of the Hudson River rather than the narrowest since planners wanted to avoid the jurisdiction of the Port Authority.Here’s the thing though: there were real differences of opinion about the project and what it should accomplish. Some people wanted a rail line, some wanted bus rapid transit, some wanted carpool lanes, and still others wanted more lanes of vehicular traffic. Nothing got done because there was absolutely no consensus either from the communities involved or from their elected leaders.

One might call a 40-year planning process dysfunctional, but another view would say that this is exactly government working as intended. Things don’t get built if there is no consensus, and that’s the value — and price — of democracy.The challenge though is that you can end up in these counter-veto game theoretic morasses (the book uses “wicked problems”), where no progress will truly ever get made because everyone has an incentive to block a project to get their vision included. Here is where leadership makes such a difference. A leader in these contexts can find points of compromise, build coalitions, set agendas and a vision, and create the momentum required to get these projects moving. Unfortunately, finding leaders in American politics is excruciatingly difficult.

- Impossibly high expectations / feature creep: Every tech product manager knows the challenges of feature creep. Another person swings by, and they have a choice feature they want added that is going to take time and resources, and has limited benefit to the rest of the user base of the product. Unfortunately, infrastructure projects face many of the same challenges.

When a megaproject looks like it has built up momentum, everyone tries to glom on to it, adding their pet project. What starts as a bridge replacement project soon morphs into a bridge replacement with a new 30-mile railroad, multiple train stations, a new bus rapid transit system, and a complete zoning overhaul for multiple counties. Yet, those extra “features” also add additional veto points and complications to the original project. They are effectively barnacles on the hull of an already slow-moving ship.

Big projects galvanize our imaginations, but they shrink under the weight of their own mass. Better to down scale these projects into more bite-sized chunks with clear goals and deliverables rather than being all things to all people.

One thing I was surprised reading about the Tappan Zee bridge is that the actual construction phase was relatively uneventful. The bridge was built mostly on time and on budget, mostly due to extreme attention from the NY governors’s office to not allow deviations (except to stop construction on July 4th so that construction wouldn’t mar riverfront BBQs).

Four years and billions of dollars to rebuild a bridge might be ridiculous, but so were the 36 years of planning that proceeded the reconstruction. Maybe that pattern isn’t true for every project, but the lesson of Politics across the Hudson is that once the government had a plan and timing on its side, it was (relatively) smooth-sailing to the finish line.

Lawyers!

Classen Rafael / EyeEm via Getty Images

Startups need attorneys to succeed, and today, Extra Crunch is pleased to start helping you find the most helpful ones in the industry.

Extra Crunch managing editor Eric Eldon has published his deep-dive package into startup law and startup attorneys today. The package will include profiles of leading attorneys who have been identified by founders as the most helpful to their startups (today’s profile focuses on Cynthia Hess). We also have attorney Daniel McKenzie writing about “How and why you should work with a startup lawyer.” Finally, Eric and his team created a comprehensive overview of all the legal issues that come with building a startup that they compiled into a handy A-to-Z guide.

Our hope is that some of the thornier issues of building a startup can be made just a bit easier if you are armed with the right, vetted information. Let us know your thoughts.

“Mo Money, Mo Problems” for SoftBank

KAZUHIRO NOGI/AFP/Getty Images

Written by Arman Tabatabai

SoftBank’s voracious spending habits might be starting to catch up to the company. According to the Wall Street Journal, the Vision Fund’s two largest investors — the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia (PIF) and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Company — are growing increasingly frustrated with the fund’s investment process, governance structure, and the exorbitant valuations and prices paid.

Apparently, dishing out billion dollar checks like Halloween candy doesn’t make you popular with the people who give you those billions of dollars.

This isn’t the first time we’ve heard angry whispers from Vision Fund investors, with previous reports suggesting SoftBank significantly pared down previous investments in WeWork and other portfolio companies after facing serious LP pushback on the check size.

Part of the LP concern over SoftBank’s laissez-faire attitude towards check writing comes down to issues of governance. As we’ve previously discussed in our attempts to unravel SoftBank’s beast of a corporate structure, SoftBank often invests in companies at the SoftBank holding company level before selling the ownership to the Vision Fund at a later date. In the follow-on transactions, the Vision Fund often ends up paying more — in some cases billions of dollars more — than the initial investment. Now, LPs are concerned that they’re getting fleeced for billions on the back end as SoftBank drives up those investment valuations.

The ownership transfer process is just one aspect of the reportedly more general investor concerns around an opaque, complex, and disorganized investment process where SoftBank figurehead Masayoshi Son can overrule any investment decision with a “Gladiatoresque thumbs-up, thumbs-down”. According to the WSJ:

Concerns about valuation of the fund’s investments are closely linked to concerns about its investment process, in particular the power wielded by Mr. Son. In recent weeks, Mr. Son overruled objections from partners within SoftBank to a Vision Fund investment valued at as much as $1.5 billion into Chehaoduo Group, a Chinese online car-trading platform, according to people familiar with the matter. Chehaoduo was accused of fraud in recent weeks by a competitor.

And as LPs are growing concerned on how money is flowing out of the Vision Fund, SoftBank is also facing pressure from regulators on the money it is bringing in. While we’ve touched on SoftBank’s “love for leverage” before, credit agencies are once again expressing concern over the Vision Fund and SoftBank’s frothy debt levels, even noting that the company’s already junk-rated credit ratings have a better chance of getting downgraded further rather than improving.

All this goes to say that while sexy headlines and frequent nine-figure-plus deals make it easy to think SoftBank has a blank check to dish out to any unicorn they please, the clock may be striking midnight for SoftBank as they face the reality of their enormous spending, which may not bode well for their hopes for a second Vision Fund.

The Overlooked Element of the Amazon HQ2 Battle

Written by Arman Tabatabai

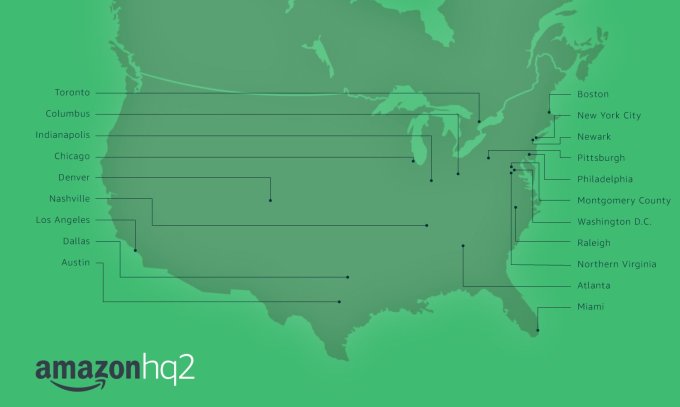

Amazon’s decision last week to halt plans to bring a second headquarters to New York City’s Long Island City neighborhood brought passionate responses from two completely schools of thought.

Some celebrated the breakup as a defeat of unjust corporate tax breaks, subsidies, and gentrification, while others threw up their hands in outrage over the disappearance of tens of thousands of jobs and future economic value that an Amazon presence would bring.

While these two arguments have been beaten to death, the remaining half of Amazon’s HQ2 development in Northern Virginia highlights an aspect of the controversial process that often gets overlooked.

Over the weekend, the Washington Post highlighted how Amazon’s pending arrival in Crystal City has helped accelerate large infrastructure projects that have long been in limbo, including public transport expansions, roadway expansions, and the construction of a new bridge to the Airport.

On top of financial investments into these projects from Amazon, the operational dates for the new HQ2 creates a timeline and has forced urgency to actually finalize plans and get these projects completed.

A huge but often overlooked political benefit of Amazon’s HQ2 process is this ability to catalyze action around public projects that otherwise may face the purgatory of public infrastructure development. While many have criticized Amazon for its auction-style selection process, many mayors and representatives from other cities that participated in the HQ2 process actually viewed the process in a positive light because they were able to unlock economic value and incentives for the city that would have been much tougher to realize otherwise.

Obsessions

- More discussion of megaprojects, infrastructure, and “why can’t we build things”

- We are going to be talking India here, focused around the book “Billonnaire Raj” by James Crabtree

- We have a lot to catch up on in the China world when the EC launch craziness dies down. Plus, we are covering The Next Factory of the World by Irene Yuan Sun.

- Societal resilience and geoengineering are still top-of-mind

- Some more on metrics design and quantification

Thanks

To every member of Extra Crunch: thank you. You allow us to get off the ad-laden media churn conveyor belt and spend quality time on amazing ideas, people, and companies. If I can ever be of assistance, hit reply, or send an email to danny@techcrunch.com.

This newsletter is written with the assistance of Arman Tabatabai from New York

from Amazon – TechCrunch https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/19/why-cant-we-build-anything/

No comments:

Post a Comment